This past December, a NOAA team, aboard the Okeanos Explorer, conducted the first of three month-long studies of the deepest parts of the Gulf of Mexico, with the dual aim of exploring the diversity of deep-water habitats and mapping the seafloor. Using a mix of remote-operated submersibles (ROVs), and shore-based instruments, the team brought back stunning images of previously unexplored areas.

Over dozens of dives, NOAA’s submersibles brought back images of deep-water creatures that had seldom been observed before.

Here, the coiled tip of a bamboo coral is pictured growing out of the sediment on the seafloor, thousands of feet below the surface.

A submersible explores a shipwreck first spotted by an offshore drilling exploration firm in 2002.

The submersible, Deep Discoverer, conducted a full archaeological survey of the wreck, collecting 3D mosaic images and analyzing the life living on it. NOAA’s researchers believe the ship is a merchant vessel dating back to around 1830.

In this image, you can see a tiny snake star, surrounded by the spiny arms of larger sea stars coiled among the branches of a coral, at a depth of 1,315 feet.

This probably isn’t like any lobster you’ve ever seen. A deep-sea squat lobster hangs out on a coral fan.

A spider crab hitches a ride on a giant isopod in the isopod’s burrow tunnel at a depth of 1,788 feet.

Giant isopods are deep-ocean varieties of pill bugs, and they’re found in cold, deep waters all over the planet. The largest specimens have been found to grow over 30 inches long, and weigh in at close to four pounds.

These two lobsters are completely blind due to their pitch-black surroundings. These ones evidently share a little burrow, but scientists aren’t exactly sure why.

A long-nosed chimaera fish drops by one of NOAA’s submersibles on a dive. Many of the researchers said this was the first time they’ve ever seen one.

Two deep-sea male red crabs are pictured here in an intense duel.

Similar to males of many species, the scientists believed these bottom-dwellers were fighting for the affection of a nearby female — but, because of a brief observation period, they can’t be certain.

Pictures here is a deep-water variety of marine smelt, from the genus Leptochilichthys.

NOAA’s researchers were astounded to see this fish at the relatively shallow depth of 2,953 feet. Typically, this species has only been observed below depths of approximately 6,000 feet.

Pictured here is a tripod fish, with parasitic isopods attached to two of its fins.

Tripod fish rest on the seafloor — facing into the current — and use their elongated fins as sensory “antenna” to catch unsuspecting prey, according to NOAA.

A Periphylla periphylla, or deep-sea helmet jellyfish, pictured colliding with the seafloor after it was startled by the bright lights from the submersible.

These jellyfish undertake a daily migration towards the surface at dusks, and back down towards the depths at dusk. The scientists suspect the creature was reacting to the bright lights on the submersible and attempted to swim down away from the light it thought was coming from the surface.

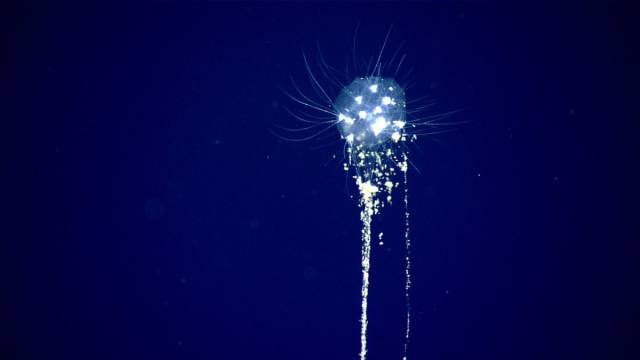

A colonial tuscarorid phaeodarean is pictured here feeding on marine snow — the nutrients (including fish excrement) that drop from shallow waters higher in the water column — at a depth of 2,300 feet.

This creature hasn’t been widely studied by scientists. It’s composed of colonies of individual cells, which secrete silica shells. The shells combine to create a fine silica mesh that surrounds the colony.

A deep-sea rendezvous: A sea cucumber and a shrimp wander past each other in the submersible’s lights.

Pictures here is an umbellula sea pen, with a mysid shrimp keeping it company.

Mysids are known as opossum shrimp because they have marsupial-like pouches. You can see this shrimp’s full brood pouch as two red dots on either side of its midsection.

This fish, aptly named a Darwin’s slimehead, is pictured swimming just a few meters off the sea-floor.

These fish, which can grow up to two feet long, can be found at depths of up to 4,000 feet in oceans around the planet.

This grumpy-looking cusk eel is pictured at a depth of 1,585 feet.

Scientists were unsure as to why this eel was so grumpy, but maybe you would be too if a strange, bright, submersible gawked at you while you were going about your daily business.

This is a sea toad, found hanging out on the sea floor at a depth of 2,428 feet.

The humble sea toad, which can move across the ocean-floor sediment with feet-like fins, had its star turn in Blue Planet II.

This cute little guy is a dumbo octopus, the deepest-dwelling octopus.

This image was taken from NOAA’s previous expedition to the Gulf of Mexico in 2014, but it was too good to leave out.

A craggy outcrop on the seafloor supports a dense community of sea stars.

A NOAA submersible encountered this ctenophore, or comb jellyfish, swimming just above the seafloor.

Barnorama All Fun In The Barn

Barnorama All Fun In The Barn