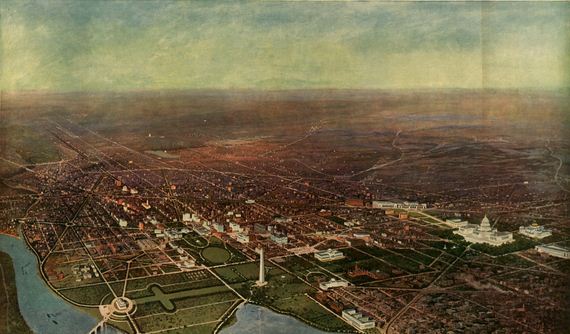

It’s hard for us Google Earth-dependent modern-day humans to conceive of, but there was once a time when we had to imagine what our towns and cities looked like from the sky. In fact, there were famous artists who specialised in creating these panoramic views of Earth, although today, it’s a lost art.

A Bird’s Eye View of Progress

The makers of these maps took the accuracy of their creations very seriously. In Panoramic Maps of Cities in the United States and Canada, the historians John R. Hébert and Patrick E. Dempsey explain the maps extensively, including how they were made. They say the artist would walk through the streets of his subject, noting every detail available, from the location of trees to how many windows each building had. They would create a kind of proxy map using their notes, and only start drawing once they had a complete survey.

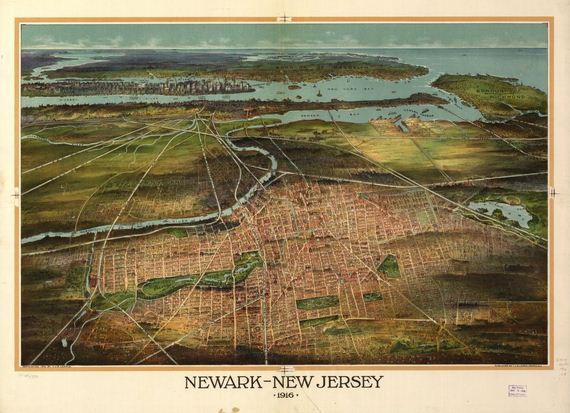

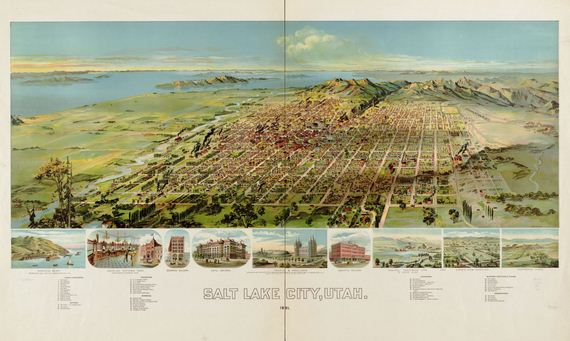

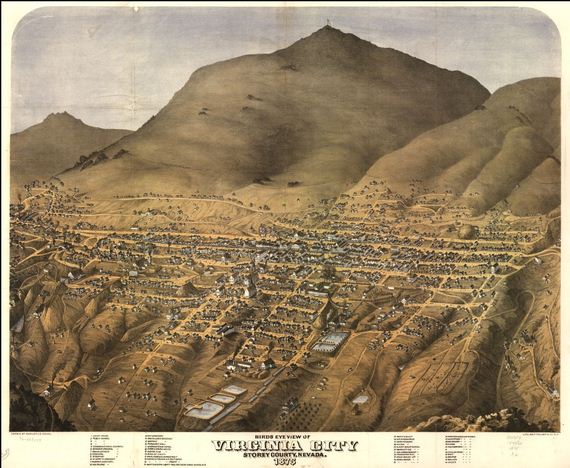

Newark-New Jersey in 1916, drawn by T. J. Shepherd Landis. Salt Lake City, Utah in 1891 by Henry Wellge, published by American Publishing Co. Birds eye view of Virginia City, Storey County, Nevada, by Augustus Koch in 1840.

The strangeness of these maps spoke to people — and in some cases, it even made them suspicious.

The grandfather of panoramic maps, a man named Thaddeus M. Fowler, was thrown in jail during World War I after residents of Allentown, Pennsylvania, suspected the stranger sketching their town was actually a German spy. Dempsey and Hébert say that Fowler included two aeroplanes and a zeppelin

to give people the false impression that the map had been drawn with help from the technological wonders of the day, which probably didn’t help his case.

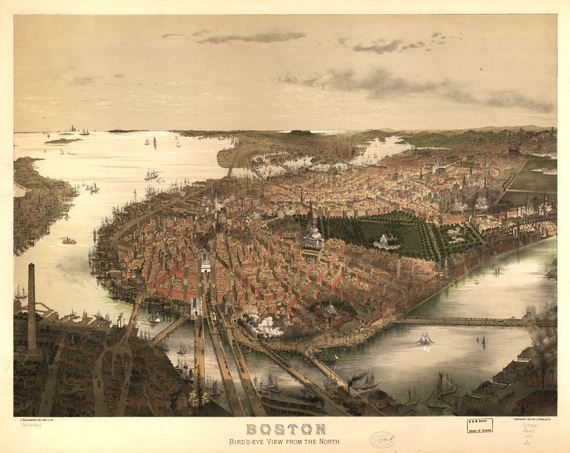

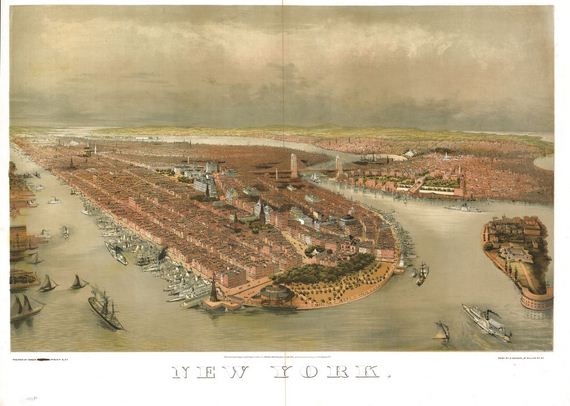

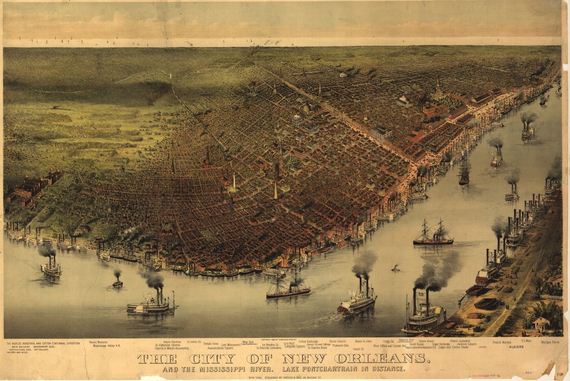

Boston bird’s-eye view from the north by John Bachmann, published by L. Prang & Co., circa 1877. New York drawn by John Bachmann and George Schlegel in 1874. The city of New Orleans, and the Mississippi River Lake Pontchartrain in distance, by Currier & Ives in 1885.

Mapping What Could Be

The United States was on its way to becoming a superpower, and these grand, sweeping visions of its cities were the best way to show them off.

“The citizen could view with pride his immediate environment and point out his own property to guests, since the map artist, for a suitable fee, obligingly included illustrations of private homes as insets to the main city plan,” say Dempsey and Hébert. “No other graphic form of this era so effectively captured the vitality of America’s urban centres.”

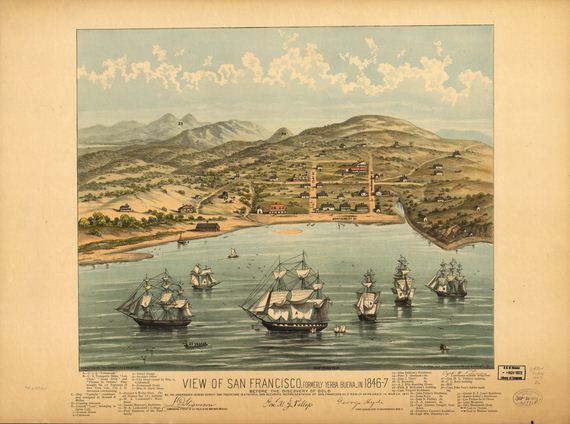

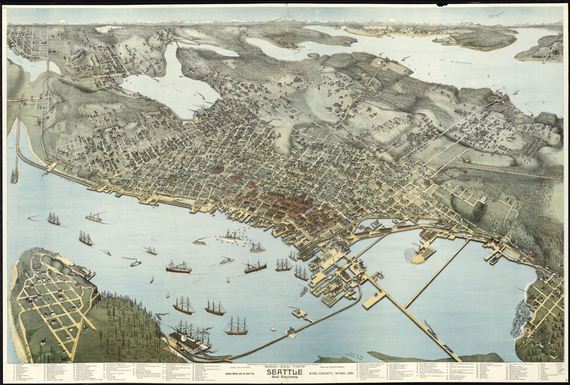

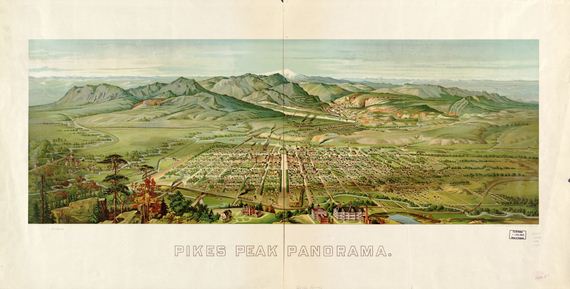

San Francisco, formerly Yerba Buena, in 1846-7, “before the discovery of gold.” Drawn by Bosqui Eng. & Print. Co. and published in 1884. Birds-eye-view of Seattle and environs King County, Wash., drawn by Augustus Koch in 1891. Pikes Peak panorama by Henry Wellge, published by American Publishing Co. in 1890.

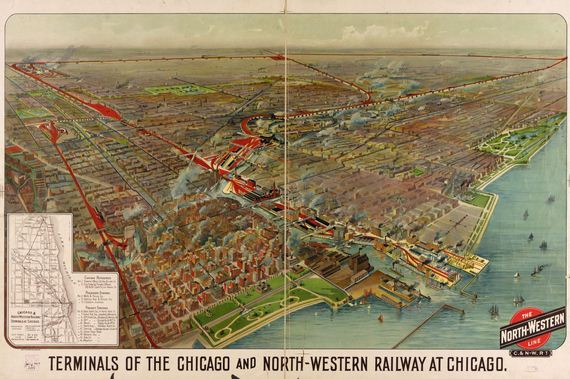

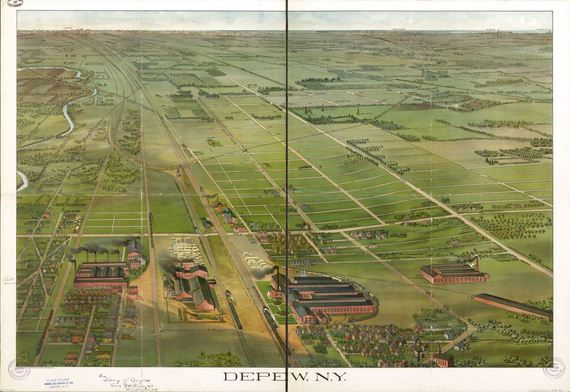

On a map of Denver, dark smoke clouds bluster from trains that run alongside a gridwork of empty plots, just waiting for entrepreneurs to snap them up. A map of Newark shows the young city in the foreground, emphasising the many roadways that lead to New York City, prominent in the background. Chicago’s already dense rat’s nest of railways and terminals are highlighted in fire engine red as they snake from Lake Michigan out into the Midwest.

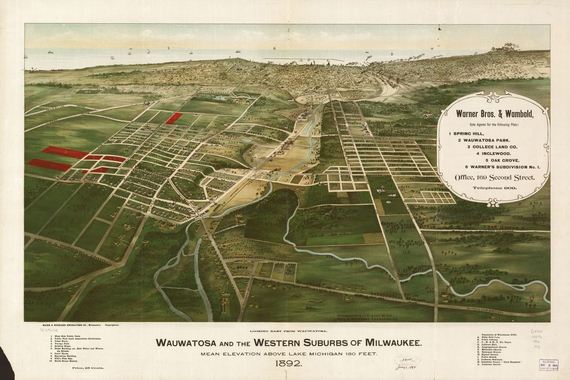

Everywhere, there’s growth and construction, half-finished streets that fade into the distance, just waiting to be extended. At the same, these artists clearly wanted to include evidence of the incredible natural beauty around them — pink and yellow clouds billow on the horizon, green, rolling fields seem to stretch for days, even the busy lakes and rivers glimmer below the thickets of ships.

Terminals of the Chicago and North-Western Railway at Chicago by Geo. H. Walker & Co., published in 1902. Wauwatosa and the western suburbs of Milwaukee 1892, by Marr & Richards Engraving Co. in 1892. Depew, New York, by Matthews-Northrup Company in circa 1898.

It’s really, really easy to lose yourself in these maps. And once you’ve looked at them for long enough, you start to understand just how different America must have seemed to the people who poured over them. The promise of endless growth, endless industry — the natural resources at hand seemed like they would last forever.

Looking at some of the details today, it’s easy to see the urban patterns that would rear their ugly heads a century later, as some cities regressed and emptied out, leaving the grids empty again. In a weird way, these maps are like archaeological documents — a geologic picture of our cities, frozen in ink and paint instead of rock.

We know what will happen as the cities continue to sprawl and grow. It wasn’t pretty. These maps are a glimpse to an imagined, and sadly very wrong, future where both growth and resources would last forever.

Barnorama All Fun In The Barn

Barnorama All Fun In The Barn